真理与真实

Truth and Reality

卜云军/Bu Yunjun

1982年出生于四川

毕业于西南交通大学艺术学院

现工作生活于北京

Bu Yunjun was born in Sichuan,

1982 He Graduated from

Art College of Southwest Jiaotong University

Now Bu Yunjun lives and works in Beijing

卜云军/Bu Yunjun

1982年出生于四川

毕业于西南交通大学艺术学院

现工作生活于北京

Bu Yunjun was born in Sichuan,

1982 He Graduated from Art College of Southwest Jiaotong University Now Bu Yunjun lives and works in Beijing

卜云军/Bu Yunjun

1982年出生于四川

毕业于西南交通大学艺术学院

现工作生活于北京

Bu Yunjun was born in Sichuan,

1982 He Graduated from

Art College of Southwest Jiaotong University

Now Bu Yunjun lives and works in Beijing

真理与真实

文/邵光华

海德格尔在《艺术作品的本源》中谈到艺术家的目标是在世界中创造一种虚空、一道间隙,并籍由此构建一处“林中空地”(Lichtung),让“存在者的真理本身置入作品”,而艺术家的工作就是协助事物慢慢走向“无蔽”,让事物不再隐藏自己。

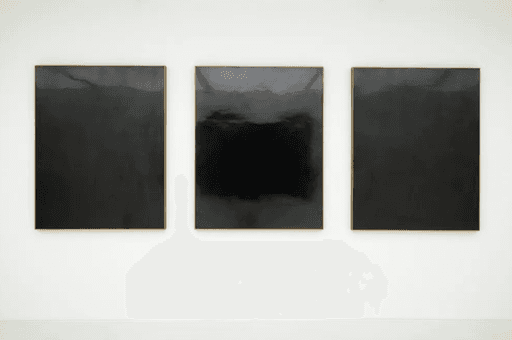

当观众走进仚東堂展厅,看到的确实是一种虚空:白色的墙壁、黑色的画作、似有若无的形象以及作品中反射出的模糊影子。一道间隙在观众与作品之间展开:没有令人目盲的五色、没有可供抓取品味的形象,眼前唯有一片浓淡自得的墨色,躲避着注视的目光,嘲笑着用来捕捉形象的镜头。

漫步在展厅之中,观众好像成了走夜路的人,睁大眼睛想要从眼前的“黑暗”中分辨出堪称为路标的存在。

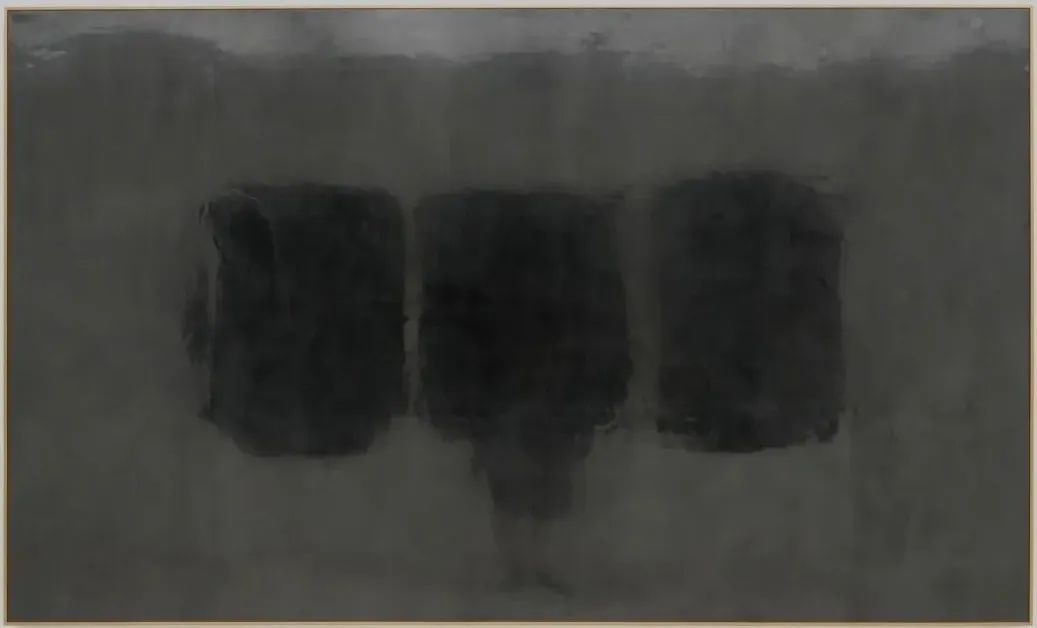

在一张张被浓墨反复晕染的绢帛之上,显露出彼此缠结的花卉,之所以能显身,是由于比周遭墨色更浓更黑,却也因此更亮;在一面面以墨为镜的《无题》系列上,观众看到反射在其中的模糊身影与周遭景象;而如果细细观察,则会发现这块镜面并非完美,它有坑洼、有擦痕、也有镜面之下蔓延的线条——犹如人的一张真实的面孔。

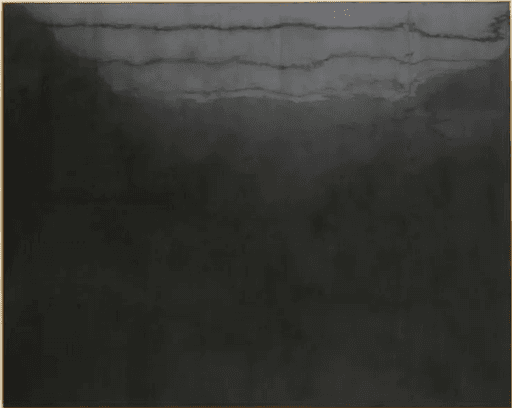

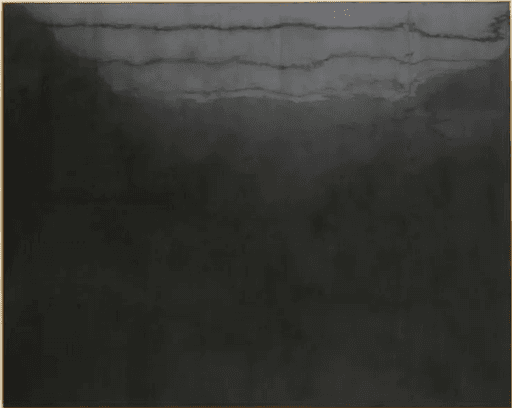

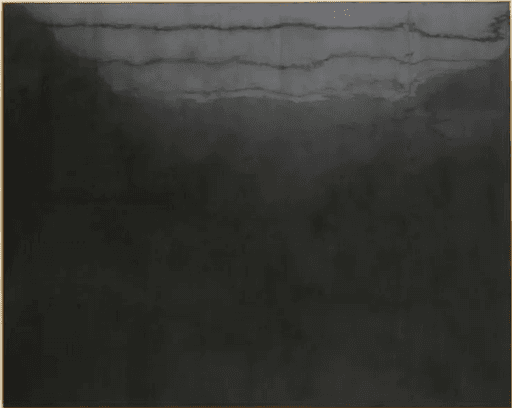

无题2022.7.19 木板水墨 300×250cm 2022

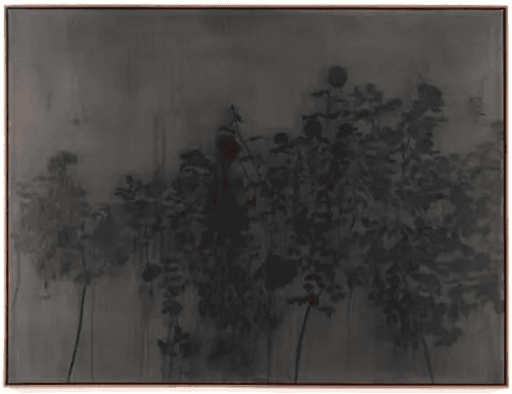

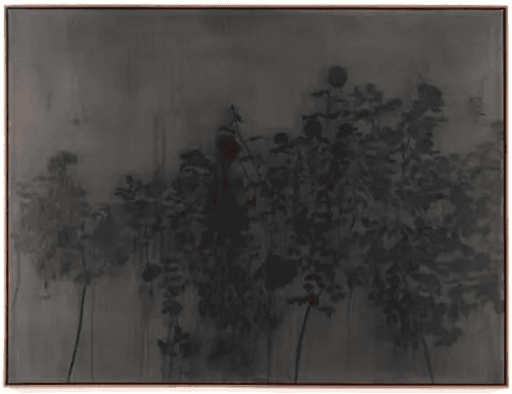

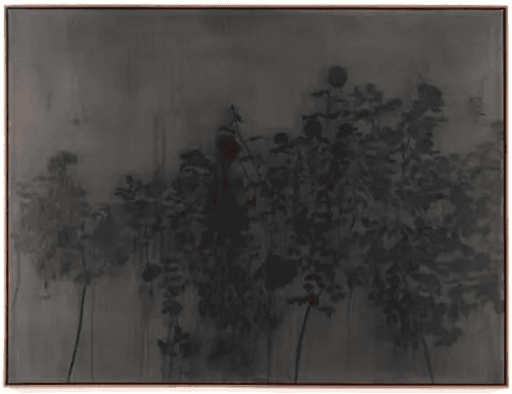

《无题-花》系列其存在犹如透过水墨滤镜后的真实世界:眼见的红花绿叶均被卜云军处理成墨色的影像,其明暗对比与真实物象一致,其缤纷色彩则被墨色以浓淡表。在这个系列的作品中,明暗和色彩虽然超出通常意义上人们对水墨画的习惯认知,同时却也完全遵循水墨画的核心逻辑:不著色彩,完全靠墨色本身的浓淡干湿来表现物象。

无题-花.7 绢本水墨 140×140cm 2022

而《无题》系列则进一步将水墨画的规则推演到了它的反面:虽然也以墨为基本材料,却并不把它视作表现万千色彩的手段,而是材料本身,通过在木板上反复涂抹、干燥、打磨等一系列“反水墨”的手法,营造出镜面的效果。

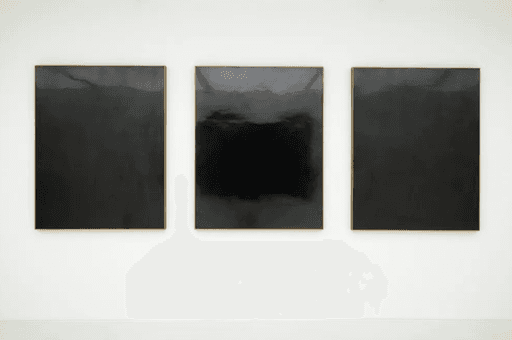

无题2022.6.10/无题2022.5.15/无题2022.5.28

木板水墨 140×110cm 2022

在这一过程中,墨本身的物理特性得到反向揭示:制墨时的两种主要原料碳和明胶以一种全新的方式展示了自身,在微观层面上水墨干燥并经过精细打磨之后,形成了光滑的镜面,在经过吸光、散射、多重反射之后形成独特的灰阶质感,墨依然是墨,却在打磨之后暂时隐居幕后,而光线本身则来到了一个介于去留之间的临界点。

很明显,卜云军在选择以墨为创作材料时,充分考虑到了它的物理特性。中国墨的存在本身就是一个矛盾体,吸光的碳与反光的明胶两者之间的奇异结合。墨中有光,光显于墨,墨同时是在否定也是在利用光。千年前的苏轼早已看出这一点,特地写道“光而不黑,固为弃物。若黑而不光,索然无神采,亦复无用。”而在水墨画的语境里,墨同样也是处于同时对物象的呈现与否定的矛盾状态,对于卜云军来说是绝佳的介入方式。

从此次展出的两个系列上,我们能看到他对于这种矛盾状态的充分利用。《无题-花》系列把水墨画的核心逻辑推演到了极致,在水墨画的临界点上对水墨画进行戏仿。绢与墨,无一不是传统水墨画的典型材料,却在卜云军的演绎下现出反叛的气质,物象本身不再由现实恩赐于我们,而是需要在反复观赏中自我显现出来;而将水墨打磨成镜面的系列作品则更显出离经叛道的意味,卜云军以破坏性的方式呈现出水墨在当下语境的新可能。

曾经宣称“绘画已死”的杜尚,曾经花费8年时间创造反绘画的《大玻璃》,在访谈录中他不认为《大玻璃》是绘画:“......上面用了许多铅,许多别的东西。他远离了传统意义上对画家的定义:用画笔、调色板、松节油,这些手段在我的生活里已经消失了。”

尽管他在水墨画的范畴内的创作手法那么地背弃传统,卜云军却带着一丝狡黠的微笑,宣称自己的作品依然属于绘画的范畴,但他的《无题》系列和杜尚的《大玻璃》一样都是“反视网膜”的,或者用他自己的话来说——“抵抗形象”。

“......我的工作最终变成了如何撕开这些具体形象,在这些裂缝中放入一些其它的东西。抵抗形象成了工作的重点,最终有了这些绘画作品。”

除了底层材料的一致性外,此次展出的两个系列作品也最终在这一理念上交汇。作为在创作时不经意浮上脑海的词语,抵抗形象可以说精准地概括了卜云军之前十年的创作之路。

以摄影进入当代艺术的卜云军,围绕着图像进行了许多尝试。从一开始他感兴趣的就是光与物、物与物乃至图像内部之间的微妙关系。为了能够从形象中解剖出这种关系,并将自己的感受注入其中,他往往把二维的图像当成是物本身,或是进行激进的裁剪、或是让它们以物的方式存在。在他看来,也许只有破坏了观众所熟知的形象之后,那些属于他自己的独特东西才会真正地显现出来。

即使在重回绘画领域之后,他的创作理念与方式依然延续着之前的道路。在以水墨为材料的这批作品中,同样延续了之前对于光线及各种“微妙状态”的关注,光在墨中所呈现的含混状态,成了他表达的最好出口。在一批起于照片并以油画棒创作的绘画中,他同样避免纠结在具体的物象上,创作时往往是先画出形象然后再覆盖掉,或者从一开始就以充满颗粒感的图像开始,尽可能地消除图像本身的魔力。

对于视觉艺术家来说,图像本身就像是塞壬的歌声,具有永恒的魔力,是拥抱还是抵抗,这是一个问题。为了能沿着自己的创作走下去,卜云军把自己绑在了名为“写实”的桅杆之上。对于之前的摄影或是如今的水墨创作,卜云军一概称之为是写实的。

然而,它们是在何种意义上属于“写实”呢?是外在物象的写实还是内在心理状态的写实?......亦或者是对于水墨传统本身与更多可能性的写实?

以水墨为媒介的创作,让卜云军不可避免地与水墨传统勾连在一起。在他的此次展览中,既有向艺术传统的回归,又有现代艺术观念的影子。两个系列作品让我们看到了卜云军对水墨传统的拥抱与弃绝。一方面作品严格遵循水墨画的核心逻辑——以水墨为媒介进行创作;然而作品的名称、外观、手法等均是对水墨传统的“弃绝”:名称并不指向物象或观念、外观也无清晰的物象可供观摩,手法上更像是一种戏谑传统的“玩世水墨主义”。

无题-花.5

绢本水墨 130×100cm 2020

尽管这两个系列作品并不符合传统水墨画的审美标准,却也没有因此陷入纯观念艺术的范畴。正如卜云军所言,它们都是写实的,也是不再被“遮蔽”的真理。当我们借助光线的变换,看清在一片墨色中慢慢浮现的花朵,或者向着影子慢慢靠近,直到意识到那些镜面上变化与破坏的痕迹,观众仿佛在此过程中进入到一个别样的感知空间之中,开始思考一些此前从未意识到的问题。

如何在弃绝五色之后,依然能够欣赏一朵花,并表现出一个传统?

如何在弃绝形象之后,去单纯地欣赏一块墨色,并以此表达真实?

这是卜云军与他背后的水墨传统共同提出的问题,需要观众自己去回答。当形象被逐渐从绘画中剥离之后,观众的欲望也被剥离,作品本身不再在观众的欲望投射下成为能指、象征、形象和内容的载体,而是单纯地存在着。它们既真实又虚幻,既写实又写意,卜云军先是以戏谑的方式回应水墨传统,然后以叛逆的姿态来对传统本身加以思考。

海德格尔所说的“真理的显现和遮蔽”,也在此时发生着:从驻足静观到察觉物象显现,本身是一个动态的过程,需要艺术家、作品和观众共同进入到游戏当中。显现必须要有光才能发生,更要经受“世界之光明”与“大地之黑暗”的永恒争斗,三者共同处在隐与显的临界点,一个意义含混的中间地带,耐心等待着显现的发生。而在观者的每一次凝视与思考中,作品的真理与真实才会“从遮蔽中走出来”,这便是走向“林中空地”的过程。

Truth and Reality

Author: Shao GuanghuaTranslation: Lin Zi

In the Origin of Art (1936), Heidegger mentioned that the goal of the artist is to create a void, fission, amidst the existing beings (Dasseined), hence opening a clear field in the wood, Lichtung. He also mentioned that when art as Dasseined, truth places itself into the work, and the artist's job is to help things move towards "revealing", make things no longer stay in “concealment”.

When the viewer walks into the venue of Xian Dong Hall, a kind of vanity comes to their sights: white walls, black paintings, obscured figures, and fuzzy shadows reflected in the works. A space opens up between the viewer and the work, but there are no flamboyant colors, no images to grasp or to taste, but a patch of ink stays in a self-sufficient place without any haste to be contacted with the viewer, evading the gaze from observation, and laughing at the camera lens used to capture images from them.

Walking in the exhibition hall, the viewer seems to experience a night walk, with their eyes wide open, trying to distinguish some kinds of landmarks from the darkness before them.

Over sheets of spun silk that are repeatedly stained with thick ink, the tangled flowers are visible because the ink depicted them is darker than the surrounding ink, hence brighter. In the 未命名 (2022) series, ink stays in a mirror-like status quo. The viewer can see the blurred figure reflected in it with the surrounding scene. With a close observation, the mirror-like surface is not a perfect one, but with potholes, scratches, and lines spreading beneath it – a resemblance not of the mirror, but a real human face.

To observe the Untitled-Flower(2021) series is like to see the real world through an ink filter: the red flowers and green leaves of a plant under Bu Yunjun’s management turn to all blank ink-colored images. The light-and-dark contrast is consistent with the vision of real plants in natural surroundings, and the vibrant colors in plants are reflected by various intensity of ink. In this series of painting, the contrast and color are not followed the customary cognition of ink painting, but they follow, at the same time, the underlying logic of it- objects are represented by the intensity and wetness of the ink itself without the involvement of colors from mineral pigments.

Furthermore, the 未命名 (2022) series further pushes the rule about ink painting to the opposition. Although the artist uses ink as the basic material to build the mirror-like surface, he does not comprehend it as a means of color representation, the artist wants to explore the material itself by repeatedly daubing on the board, drying, grinding and a series of unconventional ink painting methods.

In this process, the physical properties of the ink itself are constantly revealed. When two kinds of main raw material of carbon and gelatin reveal themselves in a new way, at the micro level, ink drying and grinding, forms a smooth mirror-like surface. After absorption, scattering and multiple reflections form unique grayscale texture, ink, after polishing, turns to a media that temporarily hides behind the scenes. The light reaches a critical point between staying and leaving.

It is obvious that Bu Yunjun has fully considered the physical characteristics of ink when he chose it as the material for his work. The very existence of Chinese ink is a paradox which consists of light-absorbing carbon and light-reflective gelatin. There is light in ink, and light shows in ink, hence ink negatively employs light. One thousand years ago, Su Shi (1137-1101) had already seen this point, hence specifically wrote "Light without blackness, solid for the waste; blackness without light, mundanity with no spirit, I prefer not to use them." In the context of ink painting, ink is also in a contradictory state of both presentation and negation of objects, which is an excellent place for Bu Yunjun to intervene.

In the two series of work here, we can see how he exploited the richness of this complication. Untitled-Flower(2021) series pushes the underlying logical of ink painting to perfection, as he imitates ink painting in a place where the ink stays in a critical place between its fullness and fully concealment. Spun silk and ink are both typical material of traditional ink painting, but under Bu Ynujun’s hands, they reveal a rare rebellious temperament, as the object is no longer a thrown being into the world, but a self-evident revealment from repeating observation. The series of works that polishes ink into mirror are even more unconventional. Bu Yunjun, subversively employs the material of ink, bringing the new possibility of ink art into a form.

Duchamp, who once declared that painting is dead, spent eight years creating La Grand Verre (1913), a work opposes all paintings. In his interview, he did not consider La Grand Verre (1913) as a painting as he said that there is a lot of lead, and a lot of other stuffs. Duchamp is so far away from the traditional definition of a painter, someone who uses brush, palette, turpentine… all of these had been lost in his life, just as Bu Yunjun is also far away from a conventional sense of an ink artist.

Although he turns his back to ink painting tradition with such a bold rebellion, Bu Yunjun stands with a sly smile, claiming that his work is still belongs to the category of painting, despite of his 未命名(2022) series, same as Duchamp's La Grand Verre (1913), is "not-for-vision", but, in his own words – “a resistance of figure".

"... My work eventually becomes how to tear apart these concrete figures and places something else in those cracks. The resistance to figures becomes the focus of the work, which are the basis of these series of painting."

Truth and Reality

Author: Shao GuanghuaTranslation: Lin Zi

In the Origin of Art (1936), Heidegger mentioned that the goal of the artist is to create a void, fission, amidst the existing beings (Dasseined), hence opening a clear field in the wood, Lichtung. He also mentioned that when art as Dasseined, truth places itself into the work, and the artist's job is to help things move towards "revealing", make things no longer stay in “concealment”.

When the viewer walks into the venue of Xian Dong Hall, a kind of vanity comes to their sights: white walls, black paintings, obscured figures, and fuzzy shadows reflected in the works. A space opens up between the viewer and the work, but there are no flamboyant colors, no images to grasp or to taste, but a patch of ink stays in a self-sufficient place without any haste to be contacted with the viewer, evading the gaze from observation, and laughing at the camera lens used to capture images from them.

Walking in the exhibition hall, the viewer seems to experience a night walk, with their eyes wide open, trying to distinguish some kinds of landmarks from the darkness before them.

Over sheets of spun silk that are repeatedly stained with thick ink, the tangled flowers are visible because the ink depicted them is darker than the surrounding ink, hence brighter. In the 未命名 (2022) series, ink stays in a mirror-like status quo. The viewer can see the blurred figure reflected in it with the surrounding scene. With a close observation, the mirror-like surface is not a perfect one, but with potholes, scratches, and lines spreading beneath it – a resemblance not of the mirror, but a real human face.

To observe the Untitled-Flower(2021) series is like to see the real world through an ink filter: the red flowers and green leaves of a plant under Bu Yunjun’s management turn to all blank ink-colored images. The light-and-dark contrast is consistent with the vision of real plants in natural surroundings, and the vibrant colors in plants are reflected by various intensity of ink. In this series of painting, the contrast and color are not followed the customary cognition of ink painting, but they follow, at the same time, the underlying logic of it- objects are represented by the intensity and wetness of the ink itself without the involvement of colors from mineral pigments.

Furthermore, the 未命名 (2022) series further pushes the rule about ink painting to the opposition. Although the artist uses ink as the basic material to build the mirror-like surface, he does not comprehend it as a means of color representation, the artist wants to explore the material itself by repeatedly daubing on the board, drying, grinding and a series of unconventional ink painting methods.

In this process, the physical properties of the ink itself are constantly revealed. When two kinds of main raw material of carbon and gelatin reveal themselves in a new way, at the micro level, ink drying and grinding, forms a smooth mirror-like surface. After absorption, scattering and multiple reflections form unique grayscale texture, ink, after polishing, turns to a media that temporarily hides behind the scenes. The light reaches a critical point between staying and leaving.

It is obvious that Bu Yunjun has fully considered the physical characteristics of ink when he chose it as the material for his work. The very existence of Chinese ink is a paradox which consists of light-absorbing carbon and light-reflective gelatin. There is light in ink, and light shows in ink, hence ink negatively employs light. One thousand years ago, Su Shi (1137-1101) had already seen this point, hence specifically wrote "Light without blackness, solid for the waste; blackness without light, mundanity with no spirit, I prefer not to use them." In the context of ink painting, ink is also in a contradictory state of both presentation and negation of objects, which is an excellent place for Bu Yunjun to intervene.

In the two series of work here, we can see how he exploited the richness of this complication. Untitled-Flower(2021) series pushes the underlying logical of ink painting to perfection, as he imitates ink painting in a place where the ink stays in a critical place between its fullness and fully concealment. Spun silk and ink are both typical material of traditional ink painting, but under Bu Ynujun’s hands, they reveal a rare rebellious temperament, as the object is no longer a thrown being into the world, but a self-evident revealment from repeating observation. The series of works that polishes ink into mirror are even more unconventional. Bu Yunjun, subversively employs the material of ink, bringing the new possibility of ink art into a form.

Duchamp, who once declared that painting is dead, spent eight years creating La Grand Verre (1913), a work opposes all paintings. In his interview, he did not consider La Grand Verre (1913) as a painting as he said that there is a lot of lead, and a lot of other stuffs. Duchamp is so far away from the traditional definition of a painter, someone who uses brush, palette, turpentine… all of these had been lost in his life, just as Bu Yunjun is also far away from a conventional sense of an ink artist.

Although he turns his back to ink painting tradition with such a bold rebellion, Bu Yunjun stands with a sly smile, claiming that his work is still belongs to the category of painting, despite of his 未命名(2022) series, same as Duchamp's La Grand Verre (1913), is "not-for-vision", but, in his own words – “a resistance of figure".

"... My work eventually becomes how to tear apart these concrete figures and places something else in those cracks. The resistance to figures becomes the focus of the work, which are the basis of these series of painting."

In addition to the consistency of the underlying materials, the two series of works in this exhibition finally converge on this idea. As a word that occasionally comes to mind during his work, resisting figures can be an accurate summarization of Bu Yunjun's path for his direction of work in the previous ten years.

Bu Yunjun, who entered contemporary art through photography, has made many attempts around images and figures. From the very beginning, he was interested in the subtle relationship between light and objects. In order to be able to dissect this relationship from the figures and inject his own feelings into it, Bu often treats two-dimensional images as objects per se, either by radical cropping or by treating images in the way of objects. In his view, perhaps only after the destruction of the familiar figures, the distinguishing uniqueness of his own can only be truly revealed.

Even after he returned to painting, Bu’s path and method continued the direction from his photography. In this group of works with ink as the main material, Bu also continues his previous attention to light and various "subtle states", and the ambiguous state of light in ink becomes the best outlet for his expression. In a series of paintings that started from photographs and were worked with oil sticks, he carefully avoided obsessing over concrete objects and figures in his work. Instead, he often paints figures first and then covers it, or start with a image full of particles. He, from the beginning, tries to reduce the magicality and enchantment from the image per se.

For visual artists, the image itself is like the song of the siren. With its eternal magic, the artist falls into a question of whether to embrace or to resist it. In order to walk his path, Bu Yunjun tied himself to a mast called realism, just like what Odysseus did in his voyage. For the previous photography or today's ink painting, Bu Yunjun calls them the works of realism.

But in what sense are they "realistic"? Is it the reality of external objects or the reality of internal mental statues quo? Or is it the realism of the ink tradition itself and the realism of bring forth more possibilities?

With the ink painting as the medium, Bu Yunjun is inevitably connected with the tradition of ink art. In his exhibition, there is not only a return to ink art tradition, but also a shape of contemporary art. The two series of works show Bu Yunjun's embracement and abandonment of the tradition of ink painting. On the one hand, the works strictly follow the underlying logic of ink painting - ink as the medium of content making; However, the name, appearance, and technique of the work are all the means of rejection of the traditional ink painting, as the name does not point to any specific concept, nor the surface contains any figures to observe. The gesture demonstrates by this series points to a "cynical ink painting" that mocks the traditional.

These two series of works do not conform to the aesthetic standards of traditional ink painting, either they do not fall into a strict category of conceptual art. As Bu Yunjun said, they are realistic, as they are truth that no longer conceals. When we see a flower slowly emerges from a piece of darkness of ink with the help of the changes of light, or approach the shadow in the surface of his work slowly until we realize that the imperfection of the surface makes it none-mirror, and that the traces of changes are actually made by you as both the viewer and the viewed, the viewer seems to enter a different perceptual space in the process, and begin to think about some questions that have never been realized before.

How do you desert the five colors and still appreciate a flower’s image while demonstrating an art tradition?

How to reveal the truth without the help of any figure by simply observing a piece of ink?

These are questions posed by Bu Yunjun and the ink tradition behind him, and it is for the viewers to answer for themselves. When the figure is expelled from the painting, so does the desire of the viewer. The work is no longer the carrier of signifier, symbol, figures and content under the projection of viewer’s desire, but the work simply exists. They are both real and illusory, realistic and freehanded. Bu Yunjun first responds to the tradition of ink painting with a playful manner, and then retrospects the tradition itself in a rebellious fashion.

What Heidegger called "the revealment and concealment of truth" is also happening at this time, from stop walking and observing, to perceiving the appearance of the work, and to realizing what is happening in the work is a dynamic process, which requires artists, works and viewers to enter the game together. Revealing takes place only in the presence of light, but also in the eternal struggle between "the light of the world" and "the darkness of the earth". Together, the three parties are at the critical point between the hidden and the visible, a middle ground of ambiguous meaning, patiently awaits for the occurrence of revealment. Only in the viewer’s gazes and contemplations, the truth and the real "come out from the concealment", which is the process of walking in a path toward Lichtung, a clearing field in the woodland.

In addition to the consistency of the underlying materials, the two series of works in this exhibition finally converge on this idea. As a word that occasionally comes to mind during his work, resisting figures can be an accurate summarization of Bu Yunjun's path for his direction of work in the previous ten years.

Bu Yunjun, who entered contemporary art through photography, has made many attempts around images and figures. From the very beginning, he was interested in the subtle relationship between light and objects. In order to be able to dissect this relationship from the figures and inject his own feelings into it, Bu often treats two-dimensional images as objects per se, either by radical cropping or by treating images in the way of objects. In his view, perhaps only after the destruction of the familiar figures, the distinguishing uniqueness of his own can only be truly revealed.

Even after he returned to painting, Bu’s path and method continued the direction from his photography. In this group of works with ink as the main material, Bu also continues his previous attention to light and various "subtle states", and the ambiguous state of light in ink becomes the best outlet for his expression. In a series of paintings that started from photographs and were worked with oil sticks, he carefully avoided obsessing over concrete objects and figures in his work. Instead, he often paints figures first and then covers it, or start with a image full of particles. He, from the beginning, tries to reduce the magicality and enchantment from the image per se.

For visual artists, the image itself is like the song of the siren. With its eternal magic, the artist falls into a question of whether to embrace or to resist it. In order to walk his path, Bu Yunjun tied himself to a mast called realism, just like what Odysseus did in his voyage. For the previous photography or today's ink painting, Bu Yunjun calls them the works of realism.

But in what sense are they "realistic"? Is it the reality of external objects or the reality of internal mental statues quo? Or is it the realism of the ink tradition itself and the realism of bring forth more possibilities?

With the ink painting as the medium, Bu Yunjun is inevitably connected with the tradition of ink art. In his exhibition, there is not only a return to ink art tradition, but also a shape of contemporary art. The two series of works show Bu Yunjun's embracement and abandonment of the tradition of ink painting. On the one hand, the works strictly follow the underlying logic of ink painting - ink as the medium of content making; However, the name, appearance, and technique of the work are all the means of rejection of the traditional ink painting, as the name does not point to any specific concept, nor the surface contains any figures to observe. The gesture demonstrates by this series points to a "cynical ink painting" that mocks the traditional.

These two series of works do not conform to the aesthetic standards of traditional ink painting, either they do not fall into a strict category of conceptual art. As Bu Yunjun said, they are realistic, as they are truth that no longer conceals. When we see a flower slowly emerges from a piece of darkness of ink with the help of the changes of light, or approach the shadow in the surface of his work slowly until we realize that the imperfection of the surface makes it none-mirror, and that the traces of changes are actually made by you as both the viewer and the viewed, the viewer seems to enter a different perceptual space in the process, and begin to think about some questions that have never been realized before.

How do you desert the five colors and still appreciate a flower’s image while demonstrating an art tradition?

How to reveal the truth without the help of any figure by simply observing a piece of ink?

These are questions posed by Bu Yunjun and the ink tradition behind him, and it is for the viewers to answer for themselves. When the figure is expelled from the painting, so does the desire of the viewer. The work is no longer the carrier of signifier, symbol, figures and content under the projection of viewer’s desire, but the work simply exists. They are both real and illusory, realistic and freehanded. Bu Yunjun first responds to the tradition of ink painting with a playful manner, and then retrospects the tradition itself in a rebellious fashion.

What Heidegger called "the revealment and concealment of truth" is also happening at this time, from stop walking and observing, to perceiving the appearance of the work, and to realizing what is happening in the work is a dynamic process, which requires artists, works and viewers to enter the game together. Revealing takes place only in the presence of light, but also in the eternal struggle between "the light of the world" and "the darkness of the earth". Together, the three parties are at the critical point between the hidden and the visible, a middle ground of ambiguous meaning, patiently awaits for the occurrence of revealment. Only in the viewer’s gazes and contemplations, the truth and the real "come out from the concealment", which is the process of walking in a path toward Lichtung, a clearing field in the woodland.

798, Beijing

Santo Hall 798

No. D10 East St.

798 Art Zone,

Chaoyang District, Beijing

Tuesday-Sunday, 10 am-6 pm

北京市朝阳区798艺术区东街D10号

Tongli, Beijing

Santo Hall TONGLI

B1, TONGLI MARKET, No.1,

Yufeng Road, Xinguozhan,

Shunyi District, Beijing

Saturdays and Sundays open to the public, by appointment for the rest of the time.

Zhengzhou, Henan

Coming soon

798, Beijing

Santo Hall 798

No. D10 East St.

798 Art Zone,

Chaoyang District, Beijing

Tuesday-Sunday, 10 am-6 pm

北京市朝阳区798艺术区东街D10号

Tongli, Beijing

Santo Hall TONGLI

B1, TONGLI MARKET, No.1,

Yufeng Road, Xinguozhan,

Shunyi District, Beijing

Saturdays and Sundays open to the public,

by appointment for the rest of the time.

Zhengzhou, Henan

Coming soon