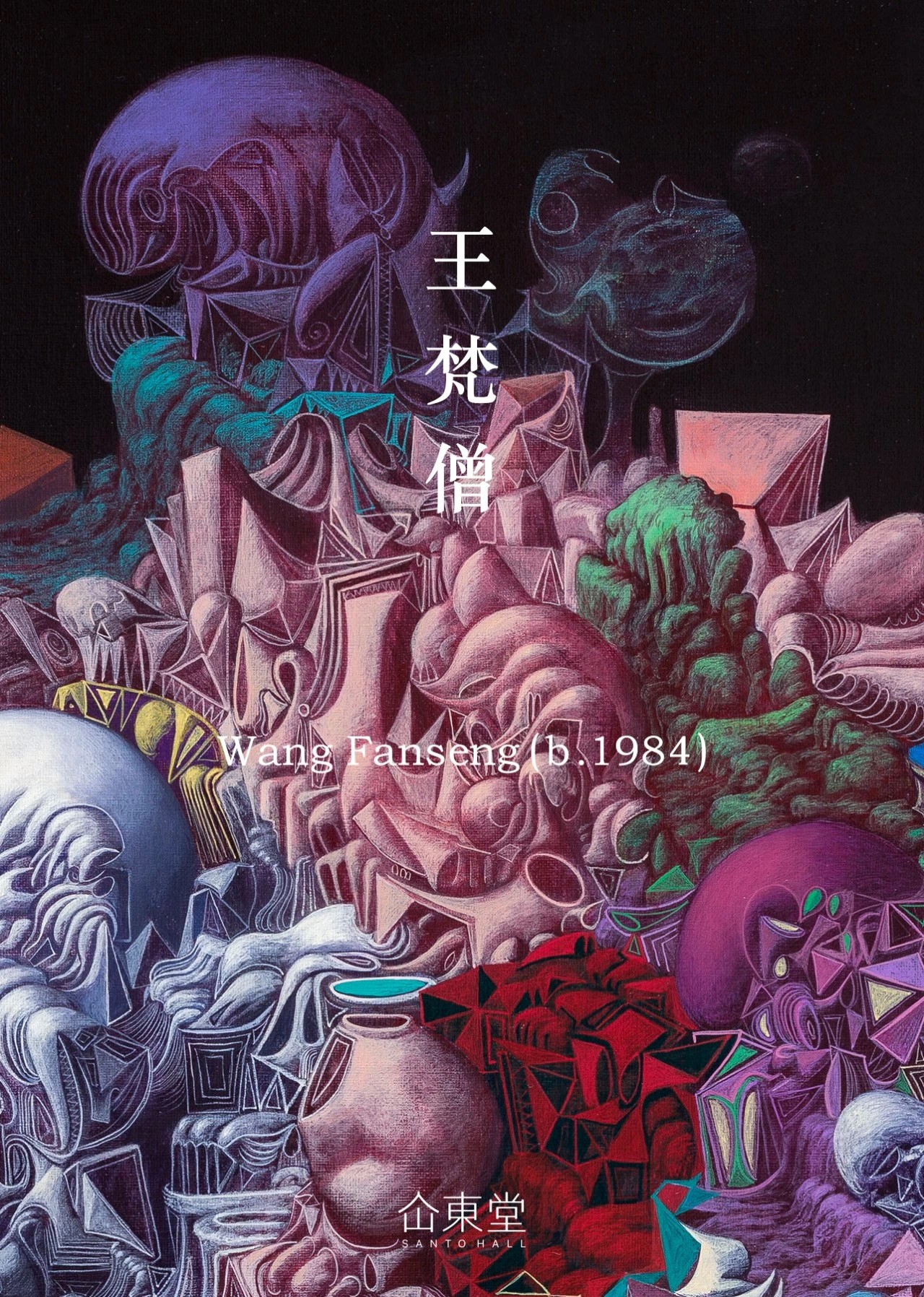

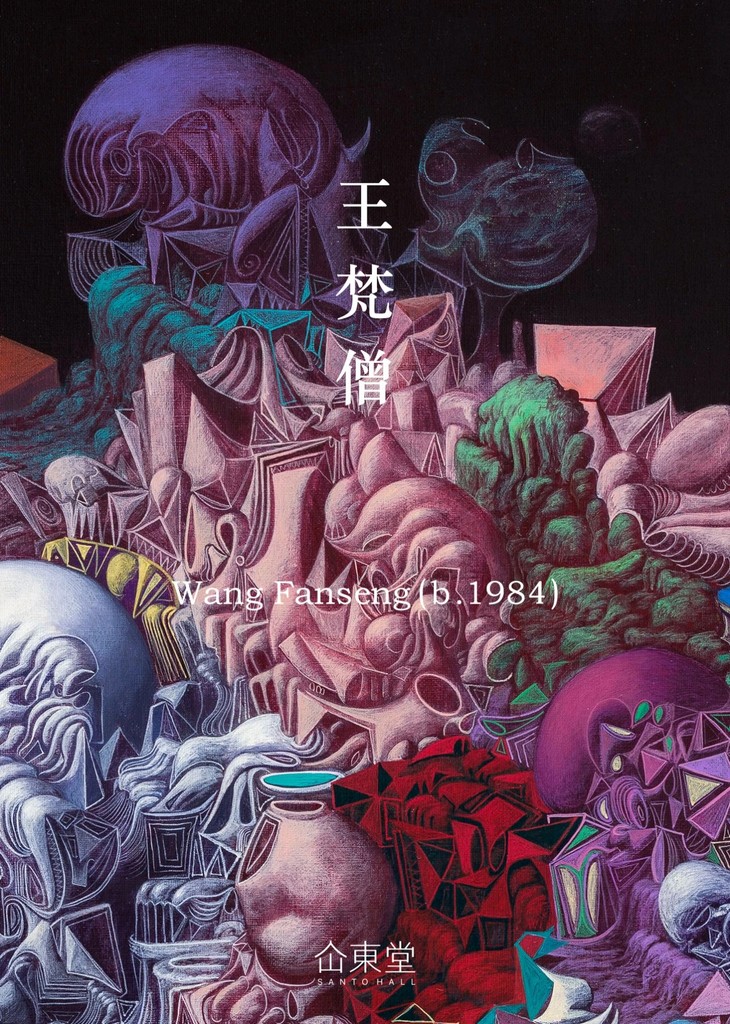

抽象的生命与形色的剧场

The Living Theater

of Abstraction

文/邵光华

"......拿画笔的那只手微微向左弯曲,指向调色板。那只熟练的手仿佛刹那间停在了画布与调色板之间,悬在了半空,被画家迷狂般的目光拦住了......" ————米歇尔·福柯 《宫娥》

在语言出现之前,一切都是模糊不清的。绘画之于梵僧,正是他用来廓清内在感受与想象世界的方式。从他绘画生涯的起点开始,那些奇山怪石、梦魇魔怪、褶皱形体与几何块面等等形象,都不过是渡人过河的筏子,它们是"没有所指的能指",只有经过梵僧施以句法与语法的装配后,才能够成为艺术家感受与情绪的表达,并以其"空"来承载观者投射其中的趣味与意义。

一:抽象的生命

个展《齐谐山志》(2012)时,梵僧开始借用山水画中以"山体"承载精神性意象的传统,并进一步向前推进山体的抽象化趋势。这一点也暗合"书画同源"自觉后山水画的内在发展脉络:书法是非写实的,然而在其笔意运动中,它完美地唤起了自然的品质和生命的节奏。由宋以后绘画趋向书法化,它日益不重视具象内容,而喜欢纯粹的表现。

当董其昌表示,与真正的山水风景相比,他对“笔墨的奇妙”更感兴趣的时候,他已经停止了在其艺术中追求自然物象或叙述性意义的脚步,而把山水画当作是纯粹的形式和运动的诗篇……可以说,梵僧正是沿着董其昌等人所开辟的道路不断前进,用抽象化的笔墨风格,去表现人与事物深层的生命。

空行变,50x70cm,布面丙烯上光,2022

空行变,场景

例如作品《空行变》(2022),在巨嶂山水似的空间里,梵僧用细笔勾勒出点景人物、怪物、莫名的几何物体,山体在高度形式化的处理下,呈现出生命性与象征性的双重特征——既是作为客观物象的身体,也是作为主观投射的"山"——作为叙事性发生的场地,形象化的身体和抽象化的空间被艺术家组合成一台完整的舞剧,上演着某个文明毁灭与重生时的景象。

在诸如此类作品中,"山-身体"依然充当着联通传统与当代性以及自我意识的纽带,昔日巨嶂山水似的宏大空间感逐渐被物体相互遮挡所形成的深度空间取代,在画面整体走向平面性的同时,"肉或者菌类"一样的山体只有部分被保留下来,充当观者进入其中的入口。点景的人与物,本身变得面目模糊,也不再负担叙事性的功能,而是作为衡量的尺度,打破观者对于大小的定见。在它们的映衬下,梵僧所描绘的对象可能是大千世界中的吉光片羽,也可能是我们所希望的任何无限大的事物。

所谓”纳须弥于芥子”,在画布有限空间内,梵僧试图去容纳、表现一个宏大的世界,并用抽象化的叙事方式,制造一种风格化的意境。对梵僧来说,抽象不是理性的规划,而是一种根植于联想并带有情感性暗示的手法,变形与抽象之后,在”能指-所指”之间的链条将被打破,画面内容因此作为空无的能指,脱离所指的牵绊后而漂浮不定,继而去暗示、呼应潜意识中的某种感受。而梵僧为每张画起名的方式,也以一种隐喻的姿态,提示出他在落笔与收尾之间的所思所想。

紧那罗,100x75cm,布面丙烯上光,2022

紧那罗,场景

在名为《紧那罗》(2022)的作品中,“紧那罗”作为印度教-佛教神话中司乐的神明,对应了画面自身的律动节奏所唤起的意象;而那些漂浮在顶部的细碎物象,为整体营造出一种舒缓、轻盈的气息,与画面中几何色块规则的铺陈展开方式形成视觉性呼应。《被梦幻侵蚀的高粱河之战》(2023)中,历史以变形的面貌与梵僧再度遭遇,对他而言历史作为一种记忆在梦境中被解构,又重新被组合成一个景观,并与画面中物象的形态、排列与聚集方式、褶皱体与几何体之间的变奏所产生某种关联,最终以命名的形式成为众多"可能的所指"之一,也让画面得以进一步丰富了维度,其意义与解释经由观者不断地增殖。

解构、抽象与重新组合,作为现代主义艺术的自觉,并非梵僧独有。他的过人之处在于借用山水画"以山言志"的传统,将山水的抽象路径进一步推进,并将绘画史上关于形体、节奏、韵律与趣味的元素吸纳进来,让"山"和"身体"背后的精神得以高扬。他所刻画的"褶皱体",更像是法国哲学家梅洛庞蒂所言的"世界之肉"(Le chair du monde),一种作为世界根基,超越主客观之分的基本元素。在处理"褶皱体"这一基本元素时,梵僧倾向于不断开拓其精神性的维度。从最早的童年记忆到后来的绘画与写作实践,他从这个未被祛魅的世界中提取形式、加以变形或转换,并将自身的潜意识感受投射到其中,风景于是在他笔端萌发。

二:形色的剧场

在梵僧的绘画中,人群也是一道风景,热闹欢宴的场景被他加以解构与抽象,并以全景空间式的视角,将形体与颜色、空间与结构,演奏出一曲视觉的交响。褶皱的引入赋予了画面更多律动的可能,丰富了视觉语言上的多样,并让其笔触透露出一种高度抽象化之后的精炼,人群的衣着、肢体、动态,都被梵僧以某种形式转译成了"褶皱体"以及几何体;面对空白画布,梵僧展开的思考是视觉性的,在理性看来似乎回应了源起自超现实主义的"自动写作"。

的确,视觉也是可以进行思考的,正如福柯对委拉斯凯兹《宫娥》的分析那样,当绘画的手受控于画家"迷狂的目光",那么在眼与手的联动中,艺术家本人所承载的传统,他的审美及趣味,也将在此过程中自动地得以显现。在一种类似无意识的状态中,梵僧得以完成对画面整体"势"的营造,双手摆脱了理性的规划,自动地调配形、色、线条来实现画面不同区域之间的呼应,直至画面呈现出应有的秩序感;而为了让节奏成立,梵僧还需要在画面中引入"异质"元素,来与褶皱体形成某种对比与呼应,这就是我们看到的几何体以及空间负形。

落在草原上的星星,170x170cm,布面丙烯上光,2022

落在草原上的星星,场景

如果说"褶皱体"是梵僧用来刻画物象时的笔墨风格,那么几何形体就体现出他对于画面的理性规划;它就像交响曲中的休止符,正因其停顿令我们对某段旋律印象深刻;观看梵僧的绘画,我们也能感受到类似的旋律,几何体的铺陈就像一段华丽的歌剧中恰到好处的顿挫。因此,梵僧的绘画呈现类似咏物赋的节奏体验,同样的因物感兴,华丽铺陈,既有对物态的多重表达、也是观物方式的多样性,其不同之处在于梵僧是以抽象的手法,去描绘事物的某种潜在状态,一种被主观化的心物交融。

恒沙世界,150x200cm,布面丙烯上光,2023

恒沙世界,场景

在画面背后,往往隐藏着艺术家欲言又止的理念。比如在《恒沙世界》(2023)中,目之所及是繁复物象交织映衬在一起,在表面的混乱下,隐有秩序显现。而秩序本身就是梵僧要讲的故事——画面中褶皱体与几何体之间不同的生命轨迹,显现出尘世的的荒诞与无常。在梵僧绘画中,貌似任意一个形体被拿掉,整体结构就会坍塌。正如塞尚在自然中发现物体的”绝对轮廓“,梵僧用自己独特的"皴法"以及构图方式,在物象之间勾连出一种逻辑关系,而对世界加以抽象化的冲动,也是心与物融合的冲动。在这个形色的剧场中,梵僧既是导演,也是普通观众。这些形象被创造出来之后,它们便在自己的场域中自由的碰撞、拼接,并隐喻地指向外界,像呼唤出画作名字那般呼唤出世界的内在意义,而观者的加入不断为画面增补意义维度:可以将其当作可游可卧的传统山水空间,以点景人物作为参考,进入其中体察其博大;也可以将之视作传统山水画在抽象的道路上的又一界碑,在心物交融中欣赏其超现实的风味;更可以视作一幅幅以布局为骨架、以形色为血肉、以节奏为气韵的纯绘画。

被梦幻侵蚀的高粱河之战,60x80cm,布面丙烯上光,2023

被梦幻侵蚀的高粱河之战,场景

与以往相比,梵僧的近期绘画在消解叙事性、压缩空间感、走向平面性后,基调依然是对精神性的生命体的关注。只是它不再需要借助山水作为引子,也不需要外在的话语为其背书。当这些形体在画布上排列、铺陈的时候,画面的每个区域也都在看着它对面的人。在人与物象的对视中,生命体与画面之间的关系,就如同梅洛-庞蒂所说的那样"身体超出身体,这超出的一部分就与其他事物纠缠在一起"。而在梵僧的绘画中,表现的主题一直是身体与精神的混合体,以及它在某个刹那所呈现出的不同样态,或者说不同的变奏。

春蒐,60x80cm,布面丙烯上光,2023

春蒐,场景

因此,梵僧是一个忠实的记录者,或者说兰波意义上的"通灵者"(Voyant),而这个词在法文中的本义就是"观看/被观看",直接指明精神与物象之间交融、彼此拥有的状态。当梵僧将脑海里翻滚的形象"记录"到画布上时,观看本身就变成了一种视觉性的思考,而他所要传达的内容是从"不可知"状态而来,需要借助构图、形色、线条、明暗与节奏.....方能得以呈现。而绘画作为中介,本身是艺术家个体感受、审美趣味的载体,也是能指与所指自由游戏的场地,更是在隐喻地呼唤意义的”空无之地”,它像兰波的诗歌那样——“将从灵魂通达灵魂,概述一切,芳香、声音、色彩,思想与思想相互勾连,并引出思想。"

"......The skilled hand is suspended in mid-air, arrested in rapt attention on the painter's gaze; and the gaze, in return, waits upon the arrested gesture...... Michel Foucault Las Meninas

Before the emergence of language, everything existed in a state of obscurity. For Fanseng, painting elucidates his inner sensations and the world of his imagination. Starting from the inception of his artistic journey, the mountains, bizarre creatures, contorted forms, and geometric planes are merely rafts to ferry viewers across the river, devoid of inherent significance.

They are empty signifiers, and only through Fanseng's meticulous arrangement of syntax and grammar do they transform into the artist's expression of emotions and sentiments, and with their inherent "emptiness," they bear the whimsy and significance projected by the viewer.

I: The life of abstraction

During his solo exhibition Mountain Lore (2012), Fanseng began to borrow from the traditional depiction of "mountain" as a carrier of spiritual imagery in landscape paintings and further advanced the abstract style within. This also aligns with the inherent developmental trajectory of landscape painting and calligraphy: calligraphy, while not representational, perfectly evokes the qualities of nature and the rhythms of life in its brushwork movement. Since the Song Dynasty, paintings have leaned towards calligraphic qualities, progressively devaluing representational content in favor of pure expression.

When Dong Qichang expressed his interest in the "marvels of brush and ink" compared to genuine landscapes, he ceased pursuing natural subject matter or narrative significance in his art and viewed landscape painting as a purely formal and expressive poem of form and motion. Fanseng has been continuously developing upon the oeuvre of Dong Qichang and others, using abstract brushwork to portray life's profound essence within people and objects.

In Dakini Parinama, the vast terrain of mountains, the staffage, including people, monsters, and objects sketched with just a few strokes, naturally converges to form a particular narrative. Meanwhile, the mountain, subject to Fanseng's highly formalized style, exhibits a dual nature of vitality and symbolism. It serves as the embodiment of an objective entity and the subjective projection of a mountain. The "mountain," as the narrative site, pre-determines the tone and direction of the narrative—an apocalyptic scene set in the aftermath of a civilization's demise.

Within this series of artworks, the dualism of "mountain-body" connects tradition with the contemporary, embodying a sense of self-awareness. The vast expanse of mountains depicted in the past gradually gives way to a depth of space formed by the mutual obscuration of objects. As the overall composition of the artwork displays a two-dimensional quality, only a portion of the mountain, resembling flesh or fungi, remains preserved. It acts as an entry point for the viewer to enter and experience the lingering rhythm of different spatial perceptions. The depicted figures and objects, once distinct in their features, now become obscure, liberated from their narrative functionality, serving as measurement scales to challenge the viewer's preconception on the notions of size. Against this backdrop, the objects depicted by Fanseng may appear as ethereal fragments within the vast world or as infinitely grand phenomena we aspire to witness.

From the Buddhist belief of "Sumeru Mountain in a Mustard Seed," Fanseng strives to encompass a vast world within the confined space of the canvas. By employing an abstract narrative approach, he creates a stylized ambiance. For him, abstraction is not a rational blueprint but a technique rooted in associations and infused with emotion. The connection between the "signifier" and the "signified" is shattered through deformation and abstraction. Consequently, the artwork becomes an empty signifier, detached from the constraints of its intended meaning, suspended in an indeterminate state that hints at subconscious sensations. Additionally, Fanseng's naming of each painting serves as a suggestion, unveiling the artist's thoughts and intentions that unfold between the initial stroke and the final touch.

In Kinnarā, the deity responsible for music is a common element in Hindu-Buddhist mythology, which evokes impressions in his mind that correspond to the rhythmic movements within the artwork. The delicate fragments floating at the top create a soothing and ethereal atmosphere, visually echoing the composition's orderly arrangement of geometric color blocks.

In The Battle of Gaoliang River Eroded by Dreams, history encounters Fanseng with a transformed facade. It becomes a deconstructed memory

within dreams, only to be reconstructed into a landscape while intertwining with the objects depicted in the painting's forms, arrangements, and gatherings. The rhythms between the folded and geometric bodies further enhance this connection. Ultimately, through naming, history becomes one of the many "possible signifieds," enriching the artwork's dimensions. Its meaning and interpretation continue to proliferate through observation, expanding its significance.

Deconstruction, abstraction, and recombination, as conscious elements of modernist art, are not unique to Fanseng. What sets him apart is his utilization of the traditional concept in landscape painting known as 'speaking through mountains,' further advancing the abstract path of landscape art and incorporating elements of form, rhythm, harmony, and fascination from the history of painting. He allows the spiritual essence behind 'mountains' and 'bodies' to flourish through this approach.

In addition, the 'folded flesh' forms he depicts bear a resemblance to what the French philosopher Merleau-Ponty referred to as the 'Flesh of the world' (Le chair du monde), a fundamental element that serves as the foundation of the world, transcending the subject-object dichotomy. When dealing with this fundamental element of the 'folded flesh,' Fanseng continually explores its spiritual dimensions. From his earliest childhood memories to his later pursuits in painting and writing, he extracts forms from this enigmatic world, distorts and transforms them, and projects his subconscious sensations onto them. As a result, the landscapes bloom and flourish under his brush.

II: The theater of forms and colors

In Fanseng's paintings, crowds are also a part of the scenery. Lively and festive scenes are deconstructed and abstracted by him. With a panoramic spatial perspective, he orchestrates a visual symphony of form and color, space and structure. The introduction of folds grants the artwork greater possibilities for rhythmic movement, enriching the diversity of visual language. His brushstrokes reveal a highly refined abstraction, as the attire, limbs, and dynamics of the crowds are translated by Fanseng into forms of "folded flesh" and geometric shapes. When faced with a blank canvas, Fanseng's contemplation unfolds visually from a rational perspective in response to the surrealist concept of "automatic writing."

Indeed, visuality can be subjected to reflection, just as Foucault's analysis of Velázquez's "Las Meninas" suggests. When the artist's hand is guided by their "mad gaze," their traditions, aesthetics, and interests will automatically manifest in the interplay between the eye and the hand. In a state akin to the unconscious, Fanseng is able to create an overall "momentum" of the compositiLiberatedreed from rational planning, his hands instinctively coordinate form, color, and lines to achieve harmony between different areas of the artwork until the desired sense of order is fulfilled. However, to establish a rhythm, Fanseng also introduces "heterogeneous" elements into the composition, creating contrast and resonance with the folded flesh. This is manifested through the geometric shapes and negative spaces that we observe.

If we consider the "folded flesh" forms as Fanseng's stylistic approach to depicting objects, then the geometric forms embody his rationality in planning the composition. They serve as symphonic intervals, creating a profound impression of a particular melodic segment through pauses. When observing his paintings, we can perceive this musical quality solely through our eyes, much like the well-placed cadences in a magnificent opera. Therefore, the imagery of his works provides a rhythmic experience similar to a descriptive ode with diverse perspectives. The key distinction lies in his use of abstract techniques to portray a latent state of things, a subjective fusion of the mind and the object.

Restrained ideas often lie behind his canvas, choosing to remain silent to allow the free drift of the signifier, refusing to divulge intentions. For instance, in The Sand of the Ganges, the viewer is presented with a complex interweaving of diverse objects, where an underlying order emerges hidden beneath the surface chaos. This order itself is the story that Fanseng wants to convey — the different life trajectories between the folded flesh forms and geometric shapes, revealing the absurdity and impermanence of worldly existence. In Fanseng's paintings, it seems that if any single form were removed, the entire structure would collapse. Like Cézanne's discovery of the "absolute outline" in nature, Fanseng employs his unique "wrinkling" technique and composition methods to establish a logical relationship among the objects. The impulse to abstract the world is also an impulse to merge the mind and object.

In this theater of form and color, Fanseng is both the director and an ordinary spectator. Once these images are created, they freely collide and combine within their own domain, metaphorically

pointing toward the outside world. They beckon the inner significance of the artwork, much like calling forth the name of a painting, while the viewer's engagement continuously adds dimensions of meaning to the composition. It could be a traditional landscape space where one can wander and recline, using scenic figures as reference points to immerse oneself in its vastness. Or another milestone on the abstract path of traditional landscape painting, appreciating its surreal flavor in the fusion of the mind and the object. Furthermore, it can be viewed as pure painting with the layout as the skeleton, form, color as the flesh, and rhythm as the vitality.

Fanseng's recent paintings, while dissolving narrative elements, compressing the sense of space, and moving towards flatness, still maintain a focus on the spirituality of living beings. However, they no longer need the landscape as a pretext or require external discourse to endorse it. As these forms arrange and unfold on the canvas, each area of the composition gazes at the person across from it. In the gaze between the human and the object, the relationship between the living being and the artwork is, as Merleau-Ponty said, "the body extends beyond the body, and this extension becomes entangled with other things." In Fanseng's paintings, the theme has always been the hybridity of the body and the spirit and the different manifestations or variations it presents in a fleeting moment.

Therefore, Fanseng is a faithful recorder, or, in the sense of Rimbaud, a "seer" (Voyant), where the term in French means "to observe/to be observed," directly indicating the state of blending and mutual possession between the mind and the object. When Fanseng "records" the rolling images in his mind onto the canvas, observation becomes a form of visual contemplation. The content he wants to convey originates from the realm of the "unknowable" and can only be presented through composition, form, lines, light and shadow, and rhythm.

As an intermediary, painting becomes a carrier for the artist's experiences and aesthetic preferences. It is a playground for the free play of signifiers and signifieds, and it metaphorically summons meaning in the "empty space." Like Rimbaud's poetry, it "of the soul and for the soul, it will include everything: perfumes, sounds, colors, thought grappling with thought."